While looking through various postings on the web, recently, I ran into a piece by Ben Shapiro, a regular commentator for the National Review, one of my favorite daily reading sites. I agree with much of what is written by Mr. Shapiro and his NR colleagues, but not this time.

Mr. Shapiro was defending something he apparently said on the radio about healthcare being a commodity, not something like police or fire service, which are rendered through public means. His intent, of course, is to defend how we Americans do health care business, principally in for-profit, market settings.

I believe that the choice that we Americans have made (true of politicians from both major political parties) to characterize healthcare as a market commodity is the fundamental flaw in our approach to health system reform.

Because healthcare is fundamentally unlike a market commodity, our communal insistence that market forces will somehow distribute healthcare efficiently and thus solve our major health system problems for us, causes us to repeatedly fail in health system reform. We are currently having another national moment of concern about our health system.

Now is a good time to have a discussion about whether healthcare is really a market commodity, and, if not, what it would mean for our health policy to organize our health system to deliver a public good, not a market commodity.

So, here is Mr. Shapiro’s wisdom on health care as a market commodity:

“The usual answer is that police, fire, and military are public goods, while healthcare isn’t. Public goods have two qualities: they are non-excludable and non-rivalrous. The underprovision of public goods means that government is typically expected to cover them.Non-excludable means that nobody can be prevented from using the services; non-rivalrous means that your use of the service or product doesn’t detract from my use or service of the product. The military is a more obvious public good – it protects all of us in common, and nobody can be excluded. The military can’t really protect me without protecting my neighbor.When it comes to the police and fire services, there’s something slightly more controversial – after all, there are finite police and fire resources, and if you use a firetruck and my station only has one, that makes fire services a rivalrous good. But the marginal cost to protect your neighbor is nearly zero; non-rivalrous vs. rivalrous isn’t really a binary consideration, but a spectrum, and police and fire are closer to non-rivalrous than rivalrous.So what about health care? It is both rivalrous and excludable. If there is one doctor, his services are limited. And you do not have a right to his services. The cost to adding your health care to mine is double. It is a commodity more like a hammer or an apple than it is like fire service or police service. Health care is also the most personal good you can imagine, not a public good in any real way — every solution has to be individually tailored to you, or it will not work.Why does it matter whether you label police vs. health care a public good? Public goods generally require government intervention, because the free market allows free riders. For example, if you don’t pay for the military but I do, you’re free-riding; if we all free-ride, there’s no military. That’s not true of health care. If I pay for my health care, I get my health care. Shortages are a result of too much intervention in the market, not too little. Treating a private good as a public good creates artificial shortages and creates a free-rider problem rather than solving one.Demand is also generally inelastic for police and fire — nobody calls the police and fire because they have access to them. The same isn’t true of health care, which is highly elastic — you decide what level of health care to seek based on the level of health care to which you have access.Finally, there’s the role of government itself. Police, fire, and military are all designed to protect you from violation of your rights by other human beings – from externalities. The most controversial of the three is fire services from a libertarian perspective, since nature could set your house on fire, and there’s no government role in protecting you from nature itself. By the same token the government has no role in protecting you from health failures that stem from nature. There’s a case to be made that government has a role in preventing infectious disease in the same way that it protects against fire – it’s an externality (which is why the government has typically taken the lead role in fighting infectious disease outbreak). But that’s not true for the vast majority of serious health problems, and it’s certainly not true of comprehensive health coverage.When people say that health care is a right, they’re truly undermining the functioning of the free market, creating overdemand and driving undersupply, pushing rationing. That’s precisely the opposite of the effect they’re trying to create.”

First, let me state unequivocally that I agree that there is no Constitutional right to health care. But there are many goods and services provided by government in the United States, including police and fire, which are not written into the Constitution.

For instance, there is no Constitutional right to asphalt, but I can drive from my house to the White House on roads to which I have free access. These roads are built and maintained by governments of all levels, local, state, and federal. The entire interstate freeway system was built originally, I understand, at a cost of some $400 billion.

That cost was out of the reach of even the wealthiest Americans. All of us recognize that in the context of the 21st Century, roads are essential infrastructure, or, in Mr. Shapiro’s words, a public good.

Likewise, healthcare is infrastructure required for a 21st Century society. And the cost of health care delivery is enormous—nearly an order of magnitude greater each year than the cost of the entire interstate freeway system.

Without all of us pitching in together to financially support the American health care system, no one, not even the wealthiest American, could afford the care needed. And Mr. Shapiro is wrong to state that the demand for health care is elastic.

Nobody calls for a fire truck unless there is a need. And no patient has ever asked for an appendectomy, unless there was real belly pain. Healthcare is non-excludable and non-rivalrous, contrary to Mr. Shapiro’s opinion. I guess he has never cared for anyone in an American emergency room. Everyone who comes there receives care and the marginal cost of seeing the next patient (once the hospital already exists, the doctors and nurses are there, and the CT scanner is in the building) is next to nothing.

It’s not just infectious diseases that are targeted by public health departments, but all major causes of morbidity and mortality. The delivery of all kinds of intensive care—trauma, cardiac, burn, perinatal, etc.—is best done cooperatively across an entire region. Healthcare is truly a public good.

In general, Americans have been consistently generous in supporting taxation for healthcare. In fact, Americans pay more health care taxes than do the citizens of any other nation. Nearly two-thirds of the annual health care budget in the US (now more than $3 trillion, or roughly $10,000 per American citizen per year) comes from local, state, or federal taxes. How can Mr. Shapiro call healthcare a private good when it is principally paid for with public funds?

Health care costs are busting government budgets in the US at all levels. Federal deficits on into the future, given current health care spending trends, will be principally due to rapidly rising costs for Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and other federal health programs[1].

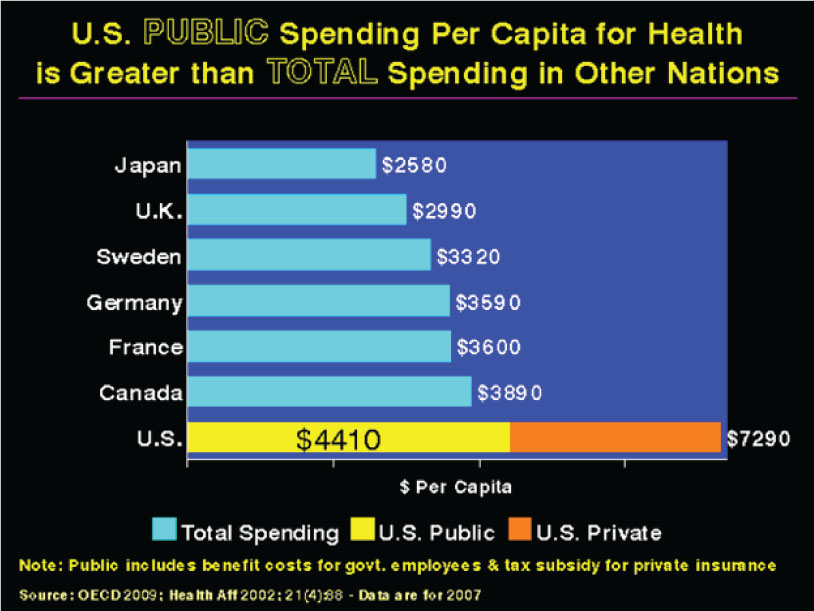

All fifty state budgets are threatened by the growth of demand for Medicaid funded health services. A state senator in Utah stated that ten years ago Medicaid required 9% of the state budget, but doubled to 18% this year and is expected to double again to 36% by the end of this decade[2]. Total health spending in the US was $2.5 trillion in 2009, accounting for 17.6% of the GDP[3]. As illustrated in the table[4] below with data from 2007, health spending on a per capita basis in the US is approximately two to three times higher than is the case in other developed nations.

Remarkably, public spending (i.e., derived from taxation) for health care is higher in the US than anywhere else in the world and, in fact, constitutes 60% of American health care spending, or $1.5 trillion (out of a total US tax revenue stream of less than $4 trillion). Public spending on health care comes at an opportunity cost. For instance, at the state level, education budgets are threatened by increasing Medicaid costs. In 2010 Utah’s lowest in the nation per pupil spending rate had to be decreased while the Medicaid budget required and received an additional $48 million[5].

Failure to improve American education over the past quarter century has resulted in an estimated $1.3 trillion to $2.3 trillion in lost (or never realized) GDP growth[6]. Family budgets, too, have been hit hard by health care costs. The US Census Bureau has found that median income for a family of four is falling and was just over $50,000 in 2009[7] while the 2010 medical cost for a typical American family of four was just over $18,000[8].

Health care costs are high in the US because of two principle problems: poor quality and inefficiency. Thomson Reuters published a $700 billion per year list of savings possible through improving health care quality[9] by reducing inappropriate care (including defensive medicine)[10], preventing injury of hospitalized patients[11], and bringing American health care services in line with known clinical science[12]. Inefficient administration of American health care financing costs up to $400 billion annually[13]. US health systems are plagued by waste due to poor quality and inefficiency because of the penchant of Americans to expect market forces to introduce accountability into all transactions, including the purchase of health care.

Health care is not a commodity that can be efficiently distributed by a market. A market exists when a completely informed buyer can freely choose to enter into a transaction with a self-interested seller without any positive externality. Market efficiency is demonstrated when demand rises as price declines. None of these conditions exist within the healthcare sector.

- a) buyers of health care lack clinical knowledge (no caveat emptor) and are not free to decide whether to purchase health services (especially in urgent settings);

- b) sellers of health services are not supposed to act in their own self-interest which is why society does not tolerate physicians and nurses whose greed pre-empts the best interests of their patients;

- c) positive externality refers to a situation when someone other than the buyer or seller has a legitimate interest in the outcome of a transaction, such as is the case when the general public has an interest in assuring the best care for a patient with a communicable disease. We have massive infusions of tax dollars into health systems because of positive externalities.

- d) the inverse relationship between price and demand does not hold for health services. No one ever bought an appendectomy because it was on sale. Demand for health services is determined by epidemiology (the frequency of disease and injury), not by price.

Lack of accountability in our health system is not a market failure, since health care is not a commodity efficiently distributed by market forces. Rather, lack of accountability in health systems is a social failure. For instance, preventable hospital injuries can be discovered and eliminated not by individual buyers (patients) but by public health agencies. The pretense of markets, so characteristic of American health policy, has created perverse incentives to deliver mediocre care in an inefficient manner[14]. Reducing poor quality and inefficiency waste will require inventing new social mechanisms to replace the failing business models which characterize the American health care delivery system.

Recently passed federal and state health ‘reform’ legislation (the Affordable Care Act and its predecessor in Massachusetts) are coverage initiatives and not the needed reform measures (for instance, read the Kaiser Family Foundation summary of the Affordable Care Act online at www.kff.org/healthreform/8061.cfm). Massachusetts officials testified before Congress one year before the passage of the Affordable Care Act that burgeoning costs made the Bay State’s health ‘reforms’ financially unsustainable. Recent projections by the Congressional Budget Office confirm that the Affordable Care Act will not prevent future “excess cost growth” in health care[15].

In summary, growth in US health care costs far exceeds any international comparison. Coverage initiatives, the standard American health policy approach over the past 50 years, ultimately fail to contain excessive growth in health care costs. The business model of private health insurance is administratively wasteful and invokes perverse incentives to deliver mediocre care. Sustainable health system reform must introduce social accountability into health care delivery while targeting improved quality and efficiency.

[1] Austin Frakt, Asst Prof, BU School of Public Health, Kaiser Health News, 1/11/11

[2] Sen. Dan Liljenquist, R-Bountiful, The Senate Site (www.senatesite.com/home/medicaid) 2/3/11

[3] Peter Landers, Wall Street Journal, 1/6/11

[4] Used with permission from Physicians for a National Health Plan

[5] Randy Shumway, Deseret News, 1/25/11

[6] Thomas Friedman, New York Times, 4/22/09

[7] US Census Bureau, 2009 American Community Survey, 9/28/10

[8] 2010 Milliman Medical Index, insight.milliman.com 5/1/10

[9] factsforhealthcare.com

[10] Kirsten Stewart, Salt Lake Tribune, 6/10/10

[11] Salt Lake Tribune, 5/5/09

[12] NEJM 2003; 348(26):2635-45

[13] Woolhandler, et al “Costs of Health Administration in the US and Canada” NEJM 349(8) 9/21/03

[14] John C. Goodman, The Wall Street Journal, 4/5/07

[15] CBO: Reducing the Deficit: Spending and Revenue Options, March 2011